At the beginning of each project, you should know your desired outcomes. That is a universal rule regardless of your project type - whether it is a software application or a new steering wheel for a car. This piece presents some aspects of software requirements engineering (but something is universal enough). Especially standards that are available and you should know, but also suggested ways to follow and technologies that might help you when defining requirements.

Requirements engineering is about defining what you want to do and partially why. It does not answer the question of how (which is the subject of design engineering). Defining requirements is (or should be) the first step in each project. The advantage of clearly defined requirements before you take the next step (designing) is clear - it can help you save a lot of time and many angry customers. Without it, you may quickly end up in the situation when you rebuild your application (or whatever you do) every few weeks, lose a lot of money on the road. It also irritates engineers who work on your project as nobody wants to do the same work repeatedly because of messy management. It is also incredibly beneficial to know the bigger picture in advance to prevent miscommunications and misunderstandings. Ultimately, weak requirements can lead to significant losses - no customer wants to re-learn how to use anything every couple of weeks. Plus, if you follow the standard way, the whole process can help you to clear your mind - you are ultimately the one who needs to know your outcomes.

What to cover, outputs, and who is in charge?

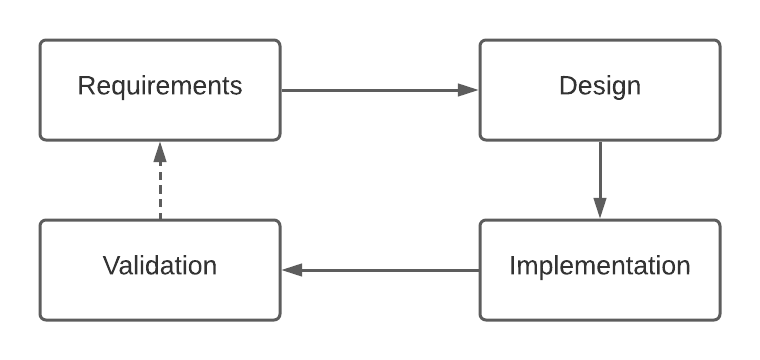

Standard software lifecycle is requirement specification, design, implementation, and validation (with some modifications, these hold true even for other systems). This logic is identical independent of the project management framework you select - whether Agile/SCRUM or Waterfall.

Also, it is essential to understand that a project that needs requirements can be almost everything - from the new application, component, or just an update of the existing application or its part. Simply, it can be everything tangible that requires more than a few steps to implement. Therefore, the recommendation is to treat everything even slightly complex as a project (of course, it is good to use some common sense).

The output of the requirements engineering process is the set of documents defining requirements from various perspectives. The most common approach is to have four documents:

- Operational Concept: this is work for the whole team. Essentially describes what the system does in plain readable language.

- Business requirements: this document is usually created by the company's management. It describes how the project fits into business.

- Stakeholders requirements: this document is created by a project manager in cooperation with key stakeholders (default stakeholders are users and vendors). It describes what is required to have in the system from each stakeholder's perspective.

- System (and Software) requirements: are defined by engineers (and product owners). From the technical perspective, this document is the most important one - it describes what the system (software) does.

Usually, the sufficient document for small projects is the software requirement specification. Usually, only big organizations can afford to have all documents carefully defined (as writing such documents is usually a time-consuming process). However, it is good to have at least system (software) requirements in advance. Furthermore, the whole team should participate if the requirement engineering process follows a standard path - that is important to prevent any potential observer biases or to miss anything important.

The IEEE standard for Requirements Engineering

The IEEE organization is famous for defining standards that are worth following. The standard pertinent to this article is ISO/IEC/IEEE 29148:2018; Systems and software engineering - Life cycle processes - Requirements engineering. It is the most popular and widespread standard for requirements engineering. The document itself is worth reading. It provides you with much helpful information regarding how to specify requirements, the optimal way to choose, the required outcomes, the optimal structure of documents, and so on. Unfortunately, despite its importance, it is not available for free - like most other IEEE standards.

Standard itself defines the need to have the following documents at the end of the requirements engineering process:

- Business Requirements Specification (BRS)

- Stakeholder Requirements Specification (StRS)

- System Requirements Specifications (SyRS)

- Software Requirements Specification (SRS)

There is also a separate definition for the Operational concept document (OpsCon) in the appendix.

The BRS describes why the system is developed, how it fits the company business plan, the underpinning processes and rules, and very generic requirements. Critically, it explains how and why envisioned (or updated) system is essential to the company - for example, why and how it helps find new customers, how it affects the growth of the company, etc. The organization and environment related to the system also have to be described in the document. Usually, the top-level management is responsible for having BRS for all crucial products. The document itself is helpful for big organizations following strict rules. However, defining BRS for a small project or a small company can be time-consuming and might not be worth the effort. The output of BRS is the input of StRS.

The StRS is another document mainly helpful when designing an extensive system (or in a bigger company). It is vital for defining stakeholders or the whole class of stakeholders. Each stakeholder can have its requirements like specific system functions, performance, constraints etc. Usually, default stakeholders are users of the system and the organization itself. This document might be beneficial if the system is a joint work of many organizations - as it is clear who wants what. Defining stakeholders requirements usually starts with mapping stakeholders' needs, which are later converted into formal requirements.

The SyRS is a helpful document even for smaller projects - sometimes it can be skipped, and SRS can be defined directly - or these two documents can be merged. Technically, there is no need to separate SRS and SyRS if the output is a software application. However, if the output includes some hardware, the situation is different. It is the essential output of the whole requirements engineering process with SRS.

Software Requirements Specification (SRS)

The SRS is the most important document in the whole series from the engineering point of view (together with SyRS as mentioned above). The central part describes what requirements must be implemented to have a working system (software). It also describes limits and restrictions that must be followed (like legal restrictions, GDPR, and physical limits or performance requirements). Simply speaking, if you want to design anything or implement a system, SRS should be the starting point of your journey as it exactly and structurally describes what the system does (or what is the plan).

The standard defines the preferred way for overall document structure. It also describes the mandatory fields related to each requirement and the language structure. Each requirement should be a simple sentence that is the composition: condition (if applicable), subject, action, object, constraints. It also has to use the word 'shall', for example:

When a user clicks on the button Submit (CONDITION), the system XYZ (SUBJECT) shall send (ACTION) a confirming email (OBJECT) within 10 minutes (CONSTRAINT).

The language restrictions of the standard are quite limiting - it is worth studying the related section a bit more carefully. The critical feature of each requirement is verifiability - someone needs to say whether this has been implemented or not in the end. Mandatory fields related to each requirement are:

- Identification: each requirement should have some ID so that you can reference it later.

- Version: if you update the requirement, you must change the version (this is omissible for small projects).

- Owner: if you have multiple stakeholders, you need to reference the correct owner.

- Priority: how essential is this requirement for a concrete stakeholder. It is usually defined by position in the table.

- Risk: an estimate of risk when implementing requirement (usually percentage).

- Rationale: answers why a particular requirement exists.

- Difficulty: estimates how difficult it is to implement the requirement.

- Type: what type (class) of requirements this is, usually defined by the position of the table in a separate subsection.

Therefore, it is beneficial to define requirements in a table with columns: ID, Requirement, Risk, Difficulty, Owner (if applicable), Version (if applicable). Priority can be defined by the position in the table and type of requirement by grouping types to separate tables. The rationale for each requirement can be explained externally (for example, in the OpsCon document). When it comes to the structure of an SRS document, the standard is not exact. It, however, offers a concrete suggestion in a separate section.

Template for SRS

You can find many suggested templates on the internet. The following is motivated by the standard. It is meaningful changing the requirements classes as you need, especially if you prefer to skip the SyRS, which contains many helpful things.

Introduction

Purpose

Mention that this is the requirement specification of a project (name), version (version number), using standard (a reference to IEEE), by an author (who is in charge).

Scope

Enumeration of what this document contains and specifies. Usually, a shortlist of SRS content for new readers.

Product overview

Brief, plain English, explanation of the system, also a description of the current state (what is implemented now, and how the system fits into it). This subsection can also include brief information about why the system is vital for the organization.

Definitions

This section contains explanations for abbreviations or some special terms (like explaining names of technologies).

References

References to all pertinent documents related to SRS. Mandatory documents (necessary for SRS) should be called normative references.

Requirements specification

Functional

These requirements describe how the system behaves and reacts to particular actions/inputs, including validation of inputs and error handling.

Interface

Define system interface - all inputs and outputs of the system, including their type, range of values, sources, relations to output and similar. In the case of REST services, this section is usually skipped, and just a reference to automatically generated documentation is added (a reference to OpenAPI schema).

Performance

Everything related to the system's performance - like how many users the system can handle, average (or on P99) response latency, amount of data to manage, maximal file sizes, computational time restrictions, and similar.

Usability

Things related to effectiveness (and how to measure it), satisfaction and avoidance of harm.

Database

Requirements for storing information include data entities and relations, integrity constraints, data availability, and similar. This is the right place where various diagrams (like very generic ERA models) can occur.

Design constraints

Define constraints reflecting external standards, legislation, various project limits, and similar limitations.

System attributes

This subsection defines requirements related to reliability, availability and security of the system.

Information related to verification and all other additional information can be added here in the form of appendices (or independent sections, if you prefer).

A suggested way for defining requirements

The requirements definition process usually starts with a kick-off meeting where the decision about starting the new project arises. Even if you work on the project independently, it is always helpful to discuss it with someone first. The outputs of first meetings are usually very raw, but they help later in the process. It is always helpful to do written documentation (Minutes Of The Meeting notes) even in the early stages. After you are aware of the raw content of the project, you can try to create the first wider description with a focus on components of the output. This will help you to map what all is needed in the project.

After you roughly know what the project is about and the top-level components, you can start creating requirements sets. The preferred approach is to use iteration and recursion in this process. Iterate through all elements and recursively define requirements to the desired depth. Usually, requirements are repetitive - especially if elements (components) of the system are similar. If it comes to the required depth, it is necessary to use common sense and cover only up to a reasonable level. However, requirements should cover every important aspect of the system, so after reading SRS, everyone should know what the system is about and how it works. Also, it is necessary to collect regular feedback from eventual users (customers) and all stakeholders during the process.

It is also worth noticing that dropping figures and schemas into the documents is always helpful. Many smart tools can help, for example, Lucidchart (paid service) or Draw.io (free). Other tools can help you keep documentation safe, for example, GitHub wiki pages that use Git to save documentation MD files (and interpret MD files online). GitHub wiki and Markdown (MD) is arguably the cleanest combination for storing and versioning your documentation. However, if you prefer a more high-level approach, Confluence or SharePoint are good choices (although Confluence is now too resource-hungry application, so the author cannot recommend it).

Summary

Defining requirements at the beginning of the project is always beneficial. It helps to clear minds and specify what exactly is needed. Ultimately, clearly defined requirements at the beginning of the project can save a lot of effort and money. The most popular standard for requirements engineering is IEEE 29148:2018. It provides a thorough description of all required processes, approaches, relevant documents and other outcomes. From the technical point of view, the most significant document is the Software requirements specification (aka SRS). After reading SRS, every engineer should know what the system does and be capable of designing it. When writing requirements documents, it is always necessary to use common sense. Also, many tools can help you keep documentation safe (like GitHub wiki or Sharepoint), other tools can help you with schemas (like Lucidchart or Draw.io).

❋ Tags: Project Management Design Essentials Performance Administration